How do you survive in a country where information about food ingredients is all in Japanese?

The first time I lived in Japan, I had a friend who was deathly allergic—and I mean Epi-pen allergic—to shellfish. She was so allergic, she’d get a reaction if she even ate food that had been cut with the same knife used for shellfish. She’d been dealing with it for years, though, and even in Japan, where seafood is a common ingredient, was able to predict what might set it off. Except…she kept getting a low-level reaction, as if she was eating something that had shellfish in it. Finally, she discovered what it was. The DAIRY products had shellfish in them. Yes, milk, ice cream, butter, cream, everything made with dairy was “calcium enriched” with ground oyster shells. Since she lived in Tokyo, she was able to drag a Japanese friend to the supermarket with her to read all the labels, and finally found an organic brand that didn’t add calcium to any of their products. But…yikes!

Hers was a weird and rare case, though—avoiding trouble in Japan isn’t hard if you know what to look for. Here’s how:

Solution #1: Get an allergy card

There is a wonderful website called foodallergycard.com where you can download a card in English and Japanese and check the boxes next to your food allergies. Carry this card with you and hand it to the waiter at any restaurant where you think you might encounter a dangerous allergen. Here’s what the card looks like:

If you are allergic to something not listed, check the box called “Other” and use this online dictionary to find the characters for the food you’re allergic to.

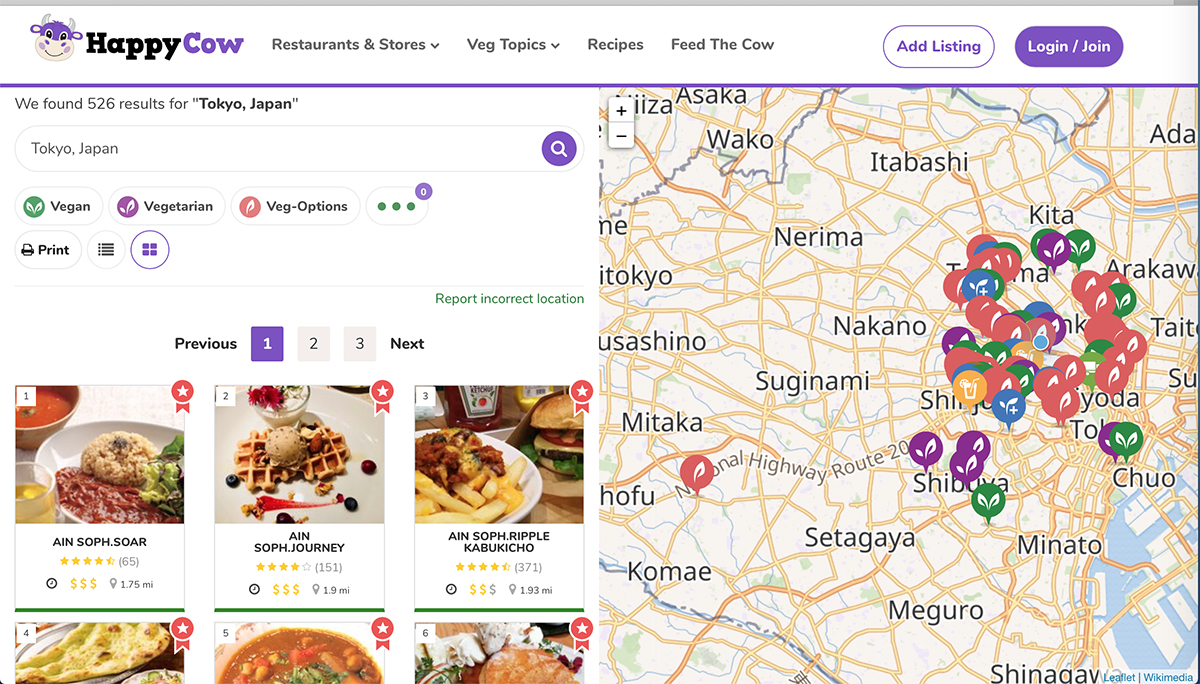

Solution #2: Depending on your allergy, you might be safer at vegan/vegetarian restaurants

Happycow.net is your friend when it comes to finding vegan/vegetarian restaurants in Japan. It’s a user-reviewed site (like Yelp) so you can read the comments before you go, to be forewarned about how strictly the restaurant observes the various no meat/no fish/no eggs/no dairy rules.

Be forewarned, though, that some “vegetarian” menu options merely avoid adding identifiable pieces of meat/fish/shellfish but still incorporate animal products (like broth) as ingredients. Beware of sauces, garnishes and foods made with batter.

Solution #3: Know your Japanese cuisine/ingredients and avoid restaurants where there are no options that work for you

The good news is that unlike “Japanese” restaurants in the West, restaurants in Japan specialize in one kind of food (i.e. sushi restaurants ONLY serve sushi and miso soup, yakitori restaurants ONLY serve grilled skewered chicken and vegetables, etc.) so even though they may have secret sauces and broths, the ingredients are pretty predictable.

If you want an excellent and thorough guide to every Japanese cuisine and its ingredients, I highly recommend Robb Satterwhite’s What’s What in Japanese Restaurants. It doesn’t tell you what restaurants to go to (although he also runs a fine restaurant/bar review site called bento.com), but it gives you an excellent feel for what you might need to be on guard for, ingredient-wise, at each kind of restaurant.

Here are some general guidelines for common restaurant types and what allergens it will be hard to avoid encountering there. (This chart is for ingredients that are actually incorporated into the foods themselves and can’t be avoided by smart ordering or left out in the cooking):

Which sneaky Japanese ingredients might trigger my allergies?

Fish 魚 (seafood that swims): Those strange rubbery “fishcakes” often found floating in Japanese soups are a processed food made from fish. The paper-thin, pink-ish or tan flakes (katsuo-bushi) that garnish many dishes are dried smoked bonito. But the most ubiquitous fish-based ingredient is dashi, the broth made from those same smoked bonito flakes. It’s an ingredient used in nearly every kind of Japanese food, and often it’s not on the radar when you ask if something has fish in it. For restaurant options where you can feel 100% safe from food with dashi in it, consult happycow.net, for vegetarian/vegan restaurant recommendations.

Shellfish 海老 or 貝 : Ground-up shells are used to add calcium to most dairy products in Japan. Chopped shrimp is sometimes added to takoyaki and okonomiyaki, so ask before ordering.

Pork 豚肉 : Ramen broth and the broth called tonkotsu (often used as a base for nabé hotpots) are both made from pork bones. Hot dogs are a common oden ingredient.

Eggs 玉子: The only common stealth use of eggs is in the batter for deep-fried foods.

Dairy: Good news! Dairy is not a traditional part of Japanese cuisine, so you’re unlikely to encounter it as an ingredient at any restaurant serving traditional dishes.

Wheat/gluten: In addition to the gluten in soy sauce (see below), the breading on deep-fried foods (panko) is made from wheat flour. Udon and ramen noodles are made from wheat flour. Most soba noodles also have wheat flour in them, but some restaurants offer a second kind of noodle called “inaka” soba, made from 100% buckwheat flour, which is gluten-free. And watch out for any pretty little cut-out shapes floating in your soup – pure gluten (called “fu“) is often colored and cut in festive shapes to add seasonal delight.

Peanuts: It’s your lucky day! Not used in traditional Japanese cuisine.

Tree nuts: Also not used in traditional Japanese cuisine.

Sesame 胡麻 or ゴマ : Sesame seeds are often used as a garnish on other foods, so scrutinize the photos on the menu or food models outside before ordering, and ask that they be left off. Sesame paste is used in the creamy dipping sauce for shabu-shabu, and sesame oil is used in most Japanese-tasting (“wafu“) salad dressings.

Soy : If you’re allergic to soy, you’re not going to have an easy time eating in Japan. Soy sauce (醤油) is used in all slightly brown sauces, broths and glazes. Tofu (豆腐) and miso (味噌) are both made from soybeans, so avoid miso soup and anything with tofu in it. Edamame (枝豆), the green beans offered as appetizers at many restaurants, are boiled, salted soybeans.

Nightshades: Tomatoes and potatoes aren’t commonly used in traditional Japanese cuisine. Peppers (ピマン) and eggplant (茄子) occur as obvious ingredients in tempura and curry rice, so you can avoid them there, but togarashi peppers are the ingredient most commonly used to give spicy Japanese food a kick, so avoid the condiment called yuzu kosho (柚子胡椒), the hotpot called motsunabe (モツ鍋) and the spice mixes called sansho (山椒) and shichimi (七味), which are the red powders inside the little containers of spices on the table at noodle restaurants.

•

I hope this helps you have a good time eating great food, because there’s plenty you can enjoy, even with allergies!

And before I go, I feel like I need to add the usual caution, which is that this is intended to be a guideline to help you navigate eating in Japan a little more easily and safely. When in doubt, ask or avoid altogether. And if you have really serious food allergies, I’m sure I don’t have to remind you to carry your emergency meds at all times.

Get more Japanese goodness straight from the source!

Subscribe to my monthly Japanagram e-magazine・° ♪・☆ It’s free!

Japanese Home Cooking recipes • Beyond Tokyo travel destinations • Seasonal Secret shopping & events • The Thing I Learned Today • Why, Japan, Why? • Monthly book or J-swag giveaway

•

Jonelle Patrick writes novels set in Japan, produces the monthly e-magazine Japanagram, and blogs at Only In Japan and The Tokyo Guide I Wish I’d Had

Of all the pins I’ve seen on pinterest, this is by far THE BEST AND THE MOST HELPFUL one! Thank you so much.

You made my day! (^_^) I’m so glad it was helpful to you!

Thank you so much for your guide! We are traveling with our 3 children to Japan and our middle child whos 3 has a shellfish allergy and this is invaluable!

It makes me so happy to hear that you found this helpful, and I hope you have an absolutely fabulous time in Japan! Thank you for taking the time to comment and tell me!